A careful dissection of the Madrid System

Posted On

Posted On

It is appropriately established that the Madrid System is bifurcated into the Madrid Agreement (1891) and the Madrid Protocol (1989). It was a welcoming introduction in the realm of trademarks for it sought to marshal and leave tangle-free the filing of trademarks abroad, which was regarded as being quintessential since trademark laws in all jurisdictions vary in practice. The system, alongside the many added benefits, enables a streamlined filing procedure with a modest fee, decreasing the quantum of applications to be filed for a single mark.

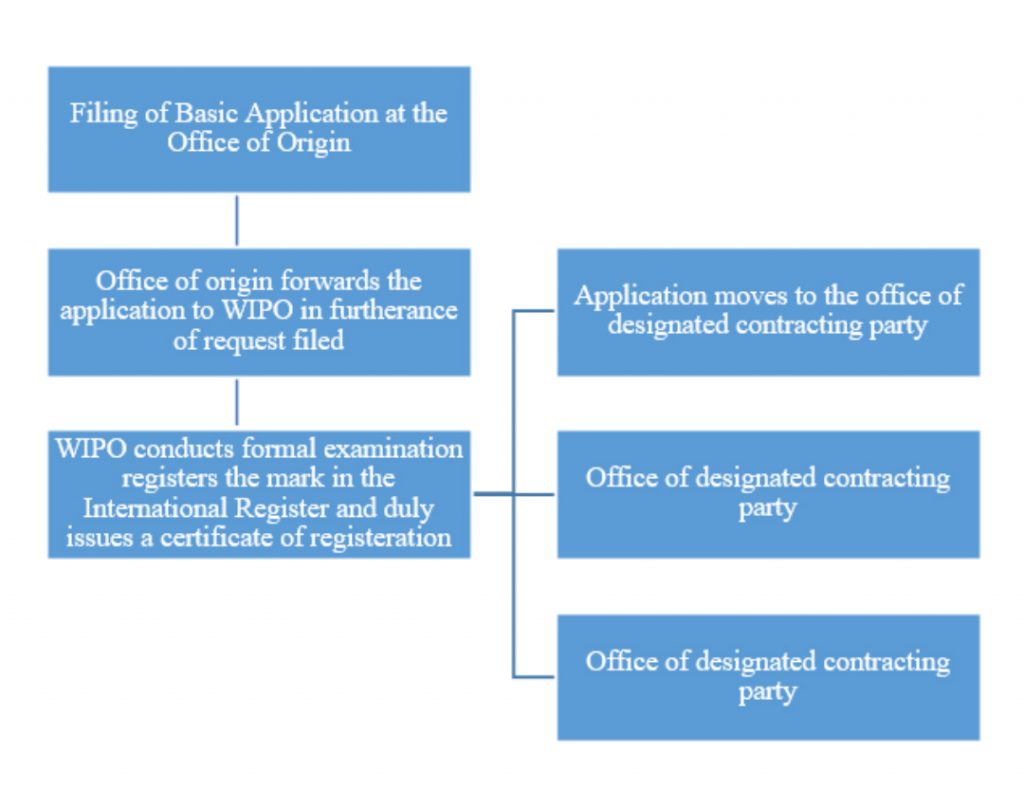

To give a brief overview, availing the benefits entailed in the Madrid System requires an applicant to file a national trademark application, also known as the ‘Basic application.’ The proprietor is then eligible to file a request for International Registration (IR) of marks, which is a means of progressing and increasing the outreach of the application to the designated states.

Fig1: Process of Filing

Although the two contribute to the creation of the Madrid system, per se, there are differences found within the two bifurcations since the Protocol aimed at overcoming the problems within the Agreement. Therefore, the key features of the Protocol can be contrasted with the Agreement as per the points of differences mentioned below:

- Primarily, as per the Madrid Protocol, a ‘Basic application’ would also suffice for the filing of an IR contrary to just the basic registration.

- Also, where the Agreement requisitioned French as the only official language, the Protocol added English and Spanish to the list of workable languages.

- Furthermore, the Protocol limits the period for notification of refusal of the IR to a period of 12 months to 18 months, where the Agreement resorted to a twelve-month window period. The Protocol enables a prompt establishment and centralized manner of controlling rights emanating out of registration.

- Lastly, the scope of protection of marks is 20 years as per the Agreement, whereas the Protocol limits it to 10 years, which is further subject to renewal in both cases.

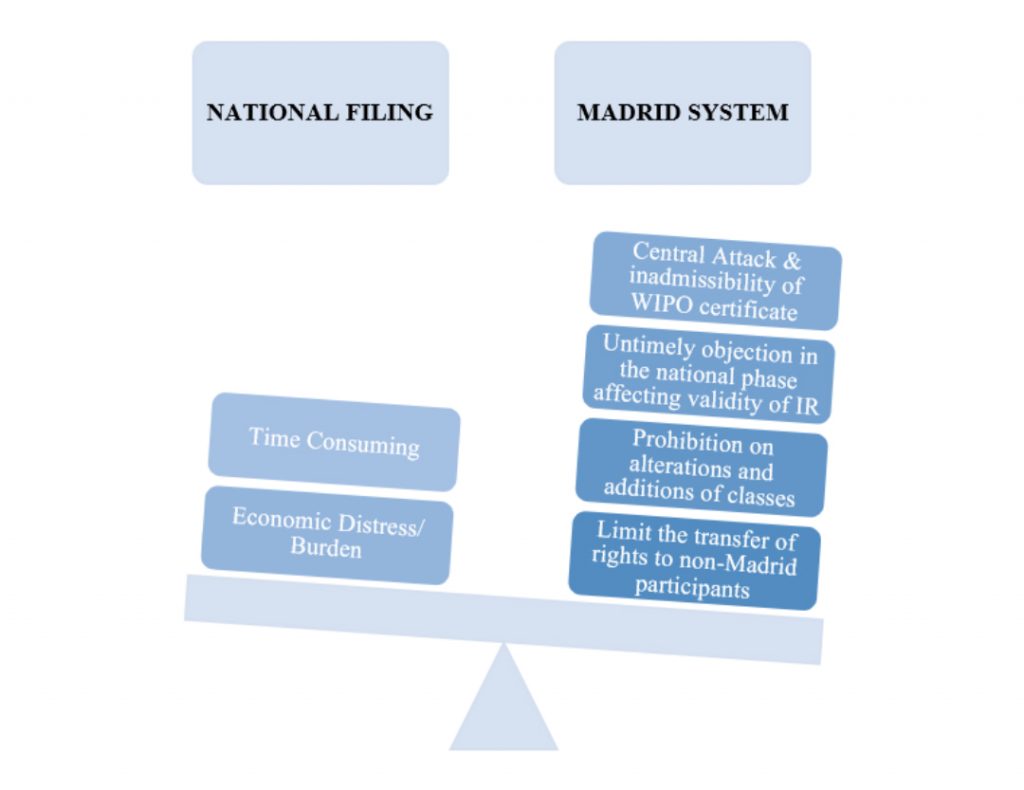

It might appear trivial to pluck out any blemishes in the system after 31 years of successful enforcement; however, it seems to be pertinent to uncover the positives as well as the negatives before actually resorting to either of the two routes for seeking protection of marks.

The gravest issues arising under the Madrid System is the issue of ‘central attack,’ which contemplates the fact that since the foundation of the application is based on one national application, in the event of cancellation or abandonment or proven invalidation, the same would naturally result in the automatic cancellation of all ancillary protections sought through the System. The situation can indeed be recovered from since the Madrid Protocol facilitates a procedure for conversion of International Registrations (IRs) into national applications for each of the designated states within three consequent months after paying due consideration. Contrary to the Madrid Protocol, the Madrid Agreement provides no such remedy. However, this hurdle has a fixed tenure of 05 years after which any harm to the basic application would not affect rights protected abroad since, after the lapse of the five-year period, IRs become independent of the national registration.

Furthermore, international registrations follow a strict timeline of processing, which is eighteen months. Quite often, the applications at the national phase are not processed by then, frequently leading to untimely objections and concerns, which could economically be very damaging for the proprietor of the concerning trademark.

Another added disadvantage here is that where on the one hand, it is popularly acclaimed that intellectual property rights are easily transferable – the Madrid System, on the other hand, limits this right only to the convention countries. Thereby, once the Madrid route is taken, assignment or transfer of rights beyond convention countries is not permissible; the proprietor then has to convert the mark into a local mark, which is not only heavy on the pocket but also a complex procedure. Thus, this could be disadvantageous where a potential opportunity from non-Madrid abiding countries is encountered for probable profitable sales or assignment of rights. Also, a handful of the countries do not acknowledge registration certificates issued under the aegis of WIPO, which ultimately implies resorting to the aid of national trademark offices for a recognized certificate at an additional cost.

In addition to this lies the problem of making modifications to the classification in the Madrid-based application. It is permissible to wipe-out, but making additions to the classification to broaden the admissibility of the said application, is not permissible. Any material or non-material changes to the mark are also not warranted.

Fig.2: Scale of disadvantages

Although it may be appealing to blindly resort to the Madrid Protocol as it offers to be a ‘one-stop-shop’ for one’s effort to trademark coupled with the benefit of a simple yet speedy examination (as acclaimed) and a cost-effective approach by delineating the need of a local council, it is imperative to take into consideration the limitations mentioned above. Hence, it is highly advisable to conduct a cost-benefit analysis of the number of jurisdictions along with the practices opted therein since all jurisdictions are not tenable to the Protocol. Also, comprehensive searches in designated jurisdictions need to be conducted to uncover prior marks, which otherwise could prove harmful in the aftermath. A concrete branding strategy ought to be put in place to avail of the maximum potential value of the trademark at hand. 👉 ✅ For more visit: https://www.kashishipr.com/