Cybersquatting of Domain Names

Posted On

Posted On

The internet boom had reverberating outcomes of which the expansion of Trademark Law was one. Consumerism and commercial activities over the internet brought with it the challenge of Domain Name disputes because of dilution and infringing acts. Although the issues exist within the realm of trademarks, they still need a thorough reading in the light of current realities.

What are Domain Names?

A domain name is a combination of names on multiple levels, an example of which is represented below:

There are three kinds of domain names as illustrated above, namely, Sub-Domain Name, Second-Level Domain Name, and Top Level Domain Name. The Top Level Domain names (hereinafter ‘TLD’) are further divided into two categories, i.e., country code TLDs (hereinafter ‘ccTLDs’) and generic Top Level Domain (hereinafter ‘gTLD’). The ccTLDs are those domain names that are specific to a country; for example, India has ‘.in’ and Australia has ‘.au’ that may or may not be available for registration to a foreign national. The gTLDs global domain names are those, which are utilized commonly without regard to any territorial limits.

Disputes Arising out of Domain Names

The Second-Level Domain (SLD) names are the usual targets forming the subject-matter of disputes in the form of what is known as cyber-squatting. Cybersquatting is a malicious practice to drive away consumers from accessing the true owner of goods. Such a practice, therefore, involves the abusive registration of a domain name in bad-faith by utilizing someone else’s trademark or soundalikes/ lookalikes of that trademark. Therefore, their main motives involve:

The Second-Level Domain (SLD) names are the usual targets forming the subject-matter of disputes in the form of what is known as cyber-squatting. Cybersquatting is a malicious practice to drive away consumers from accessing the true owner of goods. Such a practice, therefore, involves the abusive registration of a domain name in bad-faith by utilizing someone else’s trademark or soundalikes/ lookalikes of that trademark. Therefore, their main motives involve:

- Impersonation of legitimate businesses or hijacking systems by installing malware to acquire their personal credential information, including usernames, passwords, etc.;

- Selling counterfeit goods by projecting oneself as the real proprietor; and

- The most common objective is to obtain domain names to sell them to the real proprietor of trademarks at an exorbitant price. For instance, AltaVista.com was sold for $3.3 million, and HeraldSun.com was sold for $2.5 million.

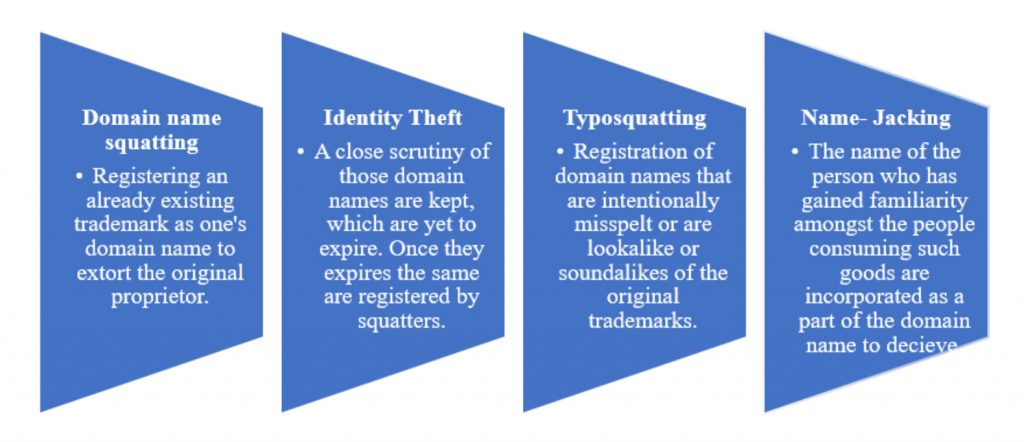

Upon the previously mentioned basis and rationale of adopting such practices, cyber-squatting is classified as:

ICANN’s Uniform Domain-Name Dispute-Resolution Policy (‘UDRP’)

The Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN) facilitates proper registration and dispute resolution as an alternative to resolution through national courts. The system of dispute resolution is known as the Uniform Domain-Name Dispute-Resolution Policy (‘UDRP’). As per the obligation imposed by ICANN upon registration of domain names, registrants undertake to not infringe upon the rights of third parties while they also submit themselves to the UDRP in case a dispute arises. However, this does not mean that either party cannot resolve disputes via court proceedings; the option of forum-shopping is given to the complainant.

The Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN) facilitates proper registration and dispute resolution as an alternative to resolution through national courts. The system of dispute resolution is known as the Uniform Domain-Name Dispute-Resolution Policy (‘UDRP’). As per the obligation imposed by ICANN upon registration of domain names, registrants undertake to not infringe upon the rights of third parties while they also submit themselves to the UDRP in case a dispute arises. However, this does not mean that either party cannot resolve disputes via court proceedings; the option of forum-shopping is given to the complainant.

The complainant ought to prove that:

- The domain name is identical or confusingly similar to a trademark in which the complainant has legitimate rights;

- The registrant has no rights or legitimate interests concerning the domain name; and

- The domain name has been registered and is being used in bad faith.

The procedure is shorter and takes up to 60 days from the date of the complaint. Also, it is much more simplified as per the rules under the UDRP Rules. The only negative is that there are only two kinds of remedies afforded under the said system, i.e., cancellation of the domain name in question or the transfer of such domain name to the rightful complainant.

These days, new gTLDs are being rapidly adopted as a lower cost and faster alternative. For this, ICANN has developed a Uniform Rapid Suspension System (URS), which is on similar lines to that of the UDRP. Although it has some specific advantages, it is pertinent to look at the negatives of the URDP:

- The decisions are not final and also do not effectuate res judicata.

- It lacks specificity, and therefore, is subject to varied forms of interpretation as also witnessed in the Wal-Mart Stores vs. Walsucks case when the use of ‘sucks’ in ‘walmartcanadasucks.com’ was construed as similar to the trademark ‘Walmart;’ while in another like case, namely, Wal-Mart Stores vs. Wallmartcanadasucks.com, it was held that use of the word ‘sucks’ along with the trade name couldn’t create confusion in the minds of the consumers concerning the original trademark.

- The UDRP system is not enacted and adopted as a part of the national legislation by many countries.

- The measures are not deterrent enough to curb such practices.

How are Different Jurisdictions Coping against the Problem of Cyber-Squatting?

As per the statistics recorded by the World Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO), the number of cases has grown by 12%, with the maximum number of cases originating from the United States, France, the United Kingdom, and Switzerland. The nature of laws heavily influences the scope of conflict; like in the US, the laws are comparatively much more stringent than that of China, which is the reason why cyber-squatting is more rampant in China. Much recently, a case was filed by Pinterest, a social-networking photograph sharing website, against a Chinese man who registered a lookalike domain name, namely, ‘www.pintersts.com,’ in utmost bad faith. An exorbitant fine of USD 7.2 million was charged from the Chinese squatter.

A) The United States of America

The United States has the Anti-cybersquatting Consumer Protection Act (ACPA), 1999, which facilitates the filing of civil suits against squatters. There are two types of actions provided for under the ACPA: one through the ‘trademark’ provision and the other through the ‘in rem’ provision. The trademark provision brings under preview those squatters who can be located within the jurisdiction of the US. However, the defendants, who cannot be located or fall beyond the court’s jurisdiction, are dealt with under the ‘in rem’ clause. The pre-requisites of bringing an action are:

- The impugned mark being dealt with is a distinctive or a famous mark;

- The domain name is identical or confusingly similar to a trademark or that it is dilutive of a famous mark; and

- The infringer registered, used, or trafficked in the domain name with evil intent or in bad faith to profit from the plaintiff’s mark.

The major shortcoming of the ACPA is that no provision for awarding damages have been made as of yet. Also, concerning the ccTLD, ‘.us,’ the control to monitor and register the same, is vested in the Department of Commerce in collaboration with a private entity, ‘NeuStar,’ which connotes to the absence of a single authority to address the concerns emanating from domain name disputes. Therefore, there lies an inherent problem of there being no uniformity of dispute resolution or a speedy procedure to resolve disputes.

B) India

India does not have a sui generis or any other law that addresses the issue of cyber-squatting. India has long witnessed the issue in one form or the other. The first instance was from Yahoo.com, the e-mail service provider, in the case of Yahoo Inc. vs. Aakash Arora & Anr, where the infringer was held liable.

However, as per the prevalent laws, cyber-squatting can be challenged by way of litigation in national courts by launching an arbitration proceeding before an ICANN-approved panel or personally sending a cease-and-desist notice to the cybersquatters. A case can also be filed with the National Internet Exchange of India (via .in registry), which is known for its speedy arbitral proceeding of delivering a judgment in a month. Therefore, the Arbitration & Conciliation Act of 1996 is deployed while utilizing the .IN Dispute Resolution Policy (INDRP).

The fundamental law dealing with digital-age problems, namely, The Information Technology Act, 2000, does not delve into the domain of cybersquatting. In the event of the absence of a definite legal proceeding, the courts deal with the issue through the application of the common-law principle of passing-off, as also witnessed in the case of Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories Ltd. vs. Manu Kosuri.

What the country needs is a law that recognizes domain-name disputes with utmost seriousness. Until then, the Trademark Law shall construe the definition of a mark in more extensive connotations under section 2(m) to include domain names as well. It will enable access to court with proper legal literature to rely on to prevent vagueness.

C) European Union

The EU has a specific provision to deal with cyber issues in the form of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). However, in practice, the out-of-court settlement of a dispute is much resorted, for which the applicant has to pay at least 1300 Euros irrespectively.

They also have a very efficient management system, which was recently launched in the previous year, in collaboration between the EU IPO (EU Intellectual Property Office) and EURid (the .EU and .ЕЮ Registry). This facility enables EU trademark applicants as well as rights holders to receive alerts once anyone uses a ‘.eu’ or ‘.eio’ domain name, which is identical or similar to their registered mark.

The UK also has no well-defined law dealing with domain name disputes, and the framework is mostly based on the law of contracts. It is the contract that binds one to the ICANN’s Uniform Dispute Resolution Policy (UDRP), which is dealt with in the next segment.

Concluding Remarks

As observed, the registration of domain names is easy and flexible as several online platforms facilitate the same, for instance, Bluehost, InMotion, Godaddy, Siteground, HostGator, Interserver, DreamHost, etc. The same has made the issue of cyber-squatting more rampant. Therefore, while opting for a short and catchy domain name might appear feasible, it could attract legal complications with heavy damages. At the same time, a legitimate proprietor of a domain name has to be aware of the risks that are created by cybersquatting and of any available defenses against it. These are a few methods that can be adopted to prevent squatting:-

- To ensure the prevention of complications, one must conduct a prior search to ascertain whether a mark should be opted for or not. Several databases facilitate the same, like Whois and EURid.

- It is always a good idea to reserve soundalikes or lookalikes or misspelled versions of one’s brand names/trade names. Therefore, pre-emptive purchasing of domain names, which are a variation of a trademark, should be opted for. However, it may not always protect a proprietor; for instance, in a case involving Philip Morris’ Marlboro, the proprietor failed to block and claim the ‘Marlboro.patry’ domain name.

- Also, a proprietor should keep the company’s domain name registration information up to date to ensure that the domain is not illegitimately acquired by a cybersquatter.

- Consider registering the name as a trademark as it will be easier to adduce it as admissible proof and establish the proprietorship over the said domain name.

- It is also a good option to purchase more than one extension over the said second-level domain name. For example, if one holds the domain name ‘www.intellectualpropertylawyers.com,’ one should also utilize other TLDs like ‘www.intellectualpropertylawyers.net,’ etc. ✅ For more visit: https://www.kashishipr.com/